ANTI-STORYTELLING IN MOVING IMAGES

Between experimental cinema, video art, and hybrid forms

Media art:

Video art was born in the 1960s out of the need to reflect on and experiment with the possibilities that the television could offer by breaking free from the reality of the television schedule. It has undergone various changes over the decades, dealing from time to time with different issues related to the ever-changing video medium.

Initially there was a clear division between cinematic art and video art, as generally the former was made with film and the latter with video (understood as an electronic signal); the “materials” explored were therefore different, as were, consequently, the results obtained. Experimental cinema used an analog “technology,” while video art, on the other hand, used an electronic and digital technology (now, however, this distinction is more difficult, if not almost impractical, due to the complete digitization of our age).

However, video art developed from experimental cinema, which grew out of none other than the artistic ferment of the Historic Avant-gardes; in the Roaring Twenties many artists, especially painters, saw in “seventh art” a new medium with which to work and expand their artistic horizons (the most famous examples are Fernand Léger’s 1924 Ballet Mécanique, 1927’s Un chien andalou, and Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s 1930 L’age d’or).

Experimental cinema: Maya Deren and Jonas Mekas

Two cornerstones of experimental cinema are Maya Deren, considered the mother of the American avant-garde film, and Jonas Mekas, the founder of the New American Cinema Group.

Maya Deren was a dancer, choreographer, photographer, and writer. Between the 1940s and 1950s she began to produce several short films in which she acted in the first person in front of the camera. In her works enigmatic and ghostly female figures move in dance steps creating atmospheres poised between Surrealism, Symbolism, and Esotericism.

Jonas Mekas, on the other hand, sees the camera as a physical extension of his body, an extroversion of his inner world. Thanks to it he is able to record in images and, absolutely spontaneously, his emotions and feelings.

He is not interested in aesthetic cleanliness nor in the “correct” use of film grammar, but rather in every possible dirtiness resulting from the chosen medium (white flashes of the end of the reel, grainy and out-of-focus images, camera movements that are not perfectly balanced…). His works are intimate, almost documentary-like portraits of his private firmament of knowledge and affection.

The intimate and personal themes typical of experimental cinema¹ will manage to also carve out a strand within later video art, however, many artists will focus on experimentation related to the medium of television.

Video art: an ever-changing language

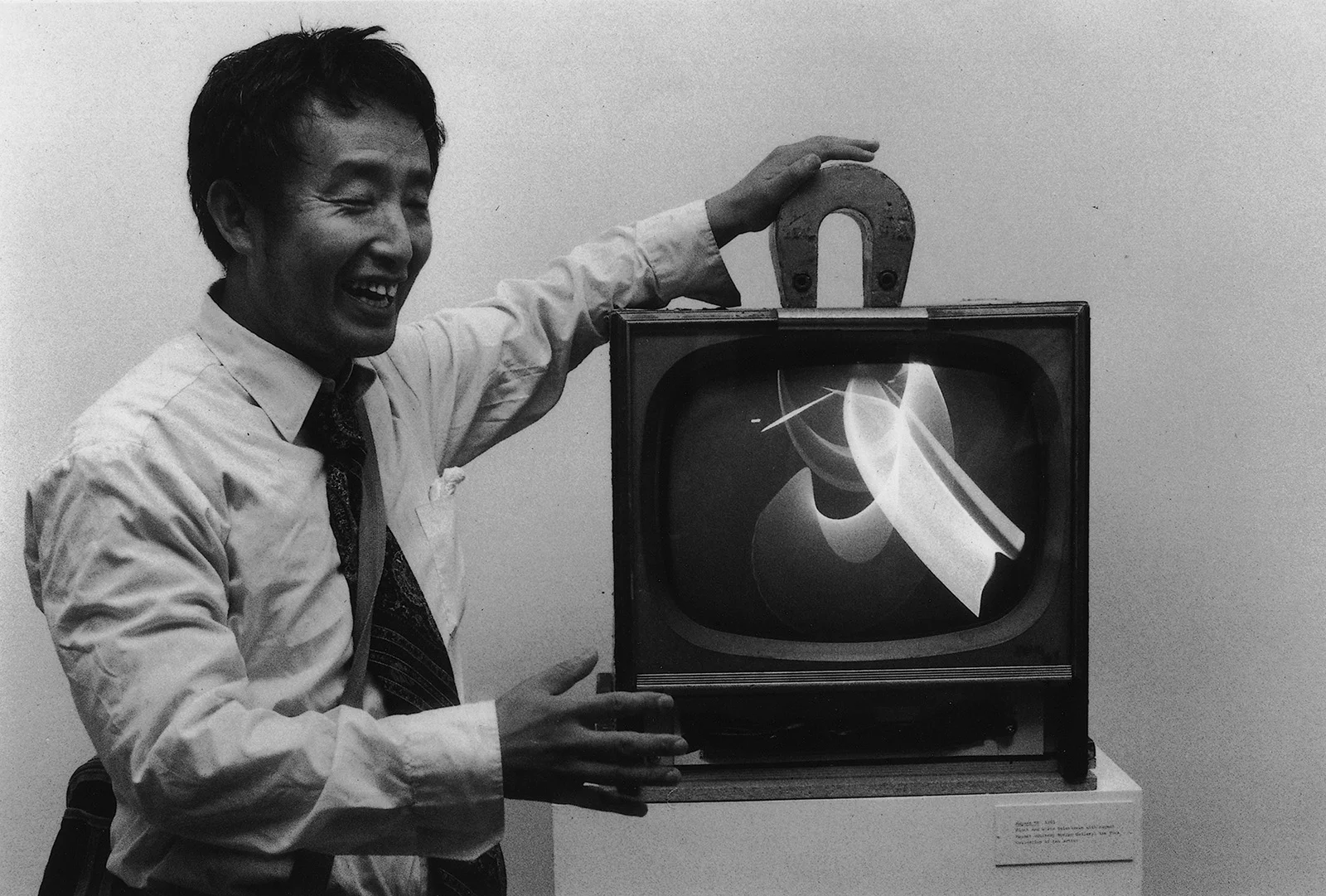

The birth of video art can be traced back to 1963, the year in which Wolf Vostell made 6 TV-Dé/Collage at the Smolin Gallery in New York and Nam June Paik created the Exposition of Music-Electronic Television exhibition in Wuppertal.

The television set is the protagonist of these early works. This new design object is capable of illuminating the surrounding space, changing it, and can remain on for an unlimited time. It also shows, for the first time in history, live images, a feature that seems to bring it incredibly close to reality, bringing the philosophical debate about the concept of reality opened up by photography and cinema to a higher plane.

Early video art, then, focused on the manipulation of television images. Through magnets and video synthesizers, the artists stimulated the video machine’s ability to autonomously generate abstract, “original,” in their own way primordial, and archetypal images of electronic language: lines and dots, distorted colors, snow, sinusoidal shapes in constant motion, all, in fact, signal disturbances.

Underlying this kind of operation was also a political discourse: there was a desire to bring the debate about reality into the spotlight, to go against the reassuringly blinkered imagery of television schedules by showing “the real face” of the machine, as if it were the hidden face of the moon.

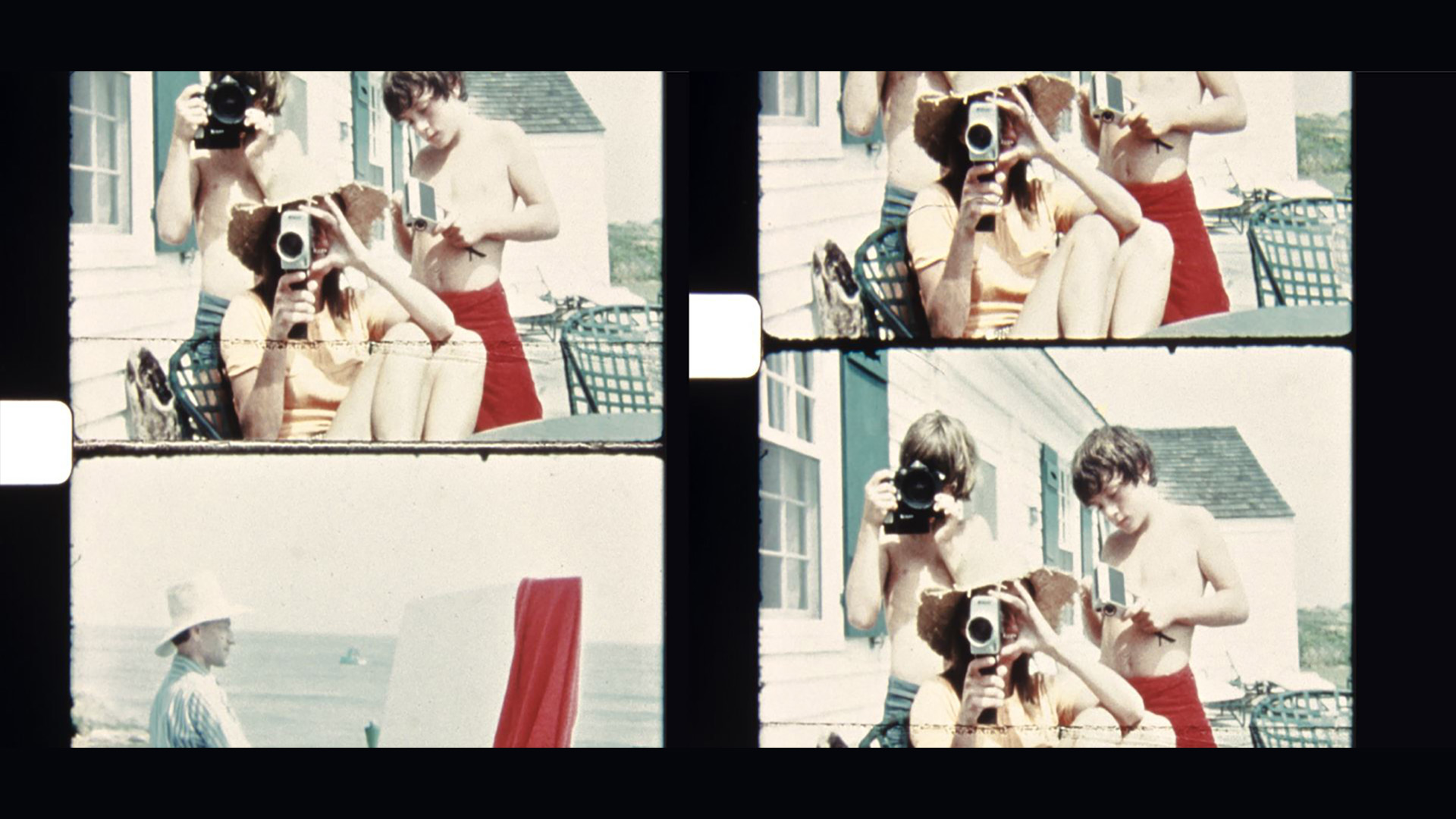

Things then changed greatly with the advent of amateur home video recording media. The marketing of the Sony Portapack in 1967, the first portable amateur video camera, finally opened up the possibility of disengaging from the aforementioned random images to create one’s own personal alphabet.

The images, now original, become testimony, paving the way for a strand of video art related to performance. Here, video regains that aspect of intimacy that had so characterized experimental cinema.

New images were added to new methods of electronic manipulation, and experimentation shifted to visual effects enabled by television-based software. Early examples of this line of research include Peter Campus’ Three Transitions, a 1973 work in which the director creates three transitions using chroma key.

In the 1980s, a further push for change came with the emergence of MTV in 1981, the first single-issue television channel dedicated to music videos. With 24-hour programming, it was constantly on the hunt for daring content that fit well with the short genre of the video clip. Video art thus became the main visual reference for new music video directors to copy and pay homage to.

It was the first time that all audiovisual experimentation (experimental cinema, animated cinema, video art, and computer art) found itself with its own television program, which allowed it to reach a wide audience.

This signaled a first step toward an osmosis between audiovisual experimentation and commercial production.

With the 1990s onward, through the advent of digital, things changed again, raising further questions: first and foremost, the reproducibility of single-channel video works.

With the arrival of the Internet, the problem of the supposed originality of the work became increasingly insistent, partly because of the loss of value in the art market of single-channel video, precisely because of its duplicability. Many artists who were employing the “single-screen” video technique began to work with video installations, reflecting on the performativity of space and audience.

The crossroads of contemporary aesthetics

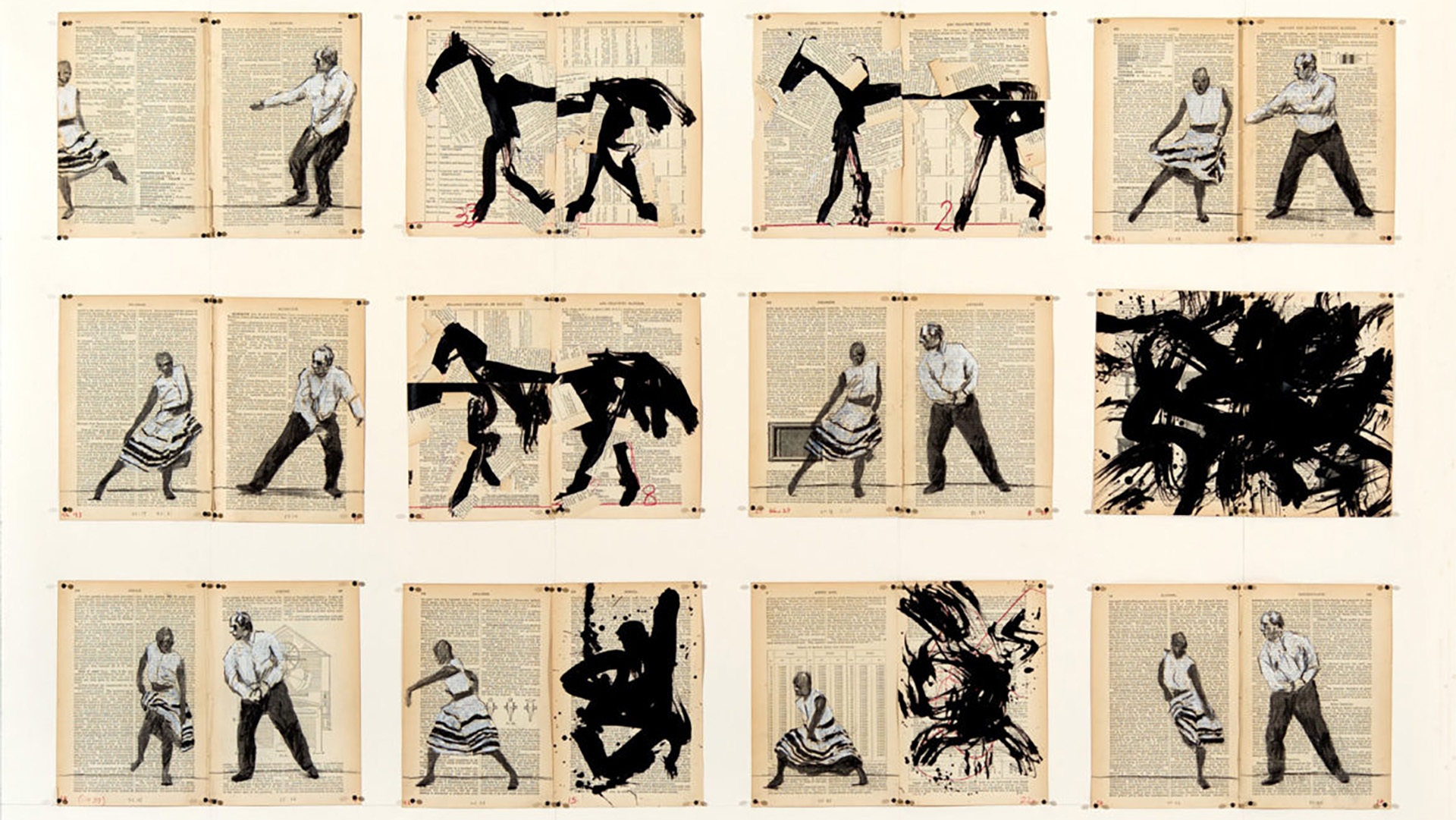

The evolution just described also sees the creation of a very pronounced aesthetic split: on the one hand, there is a tension toward an ultra-defined, clean and precise image; on the other hand, there is a desire to return to “original” cinema, to a vintage and more “artisanal” aesthetic (think of William Kentridge’s animated films, which originate from charcoal drawings).

This tension reaches to the present day. Today we see a contrast between the continuous technical refinement tending toward the highest possible definition, the recovery of the aesthetics of film, and its “smears” (tears, burns, underexposures), along with a “dirty” use of the camera.

We saw this clearly working with Emilio Isgrò, when during our first talks he specified that aesthetic cleanliness did not necessarily have to be sought. For the artist, error and imperfection were elements to take into consideration.

It is clear that today’s mass production tends toward aesthetic perfection, and if originally video art was underground, it has now become so widespread, expanded, and frayed that it has become almost mainstream and sees the limits of its own identity blurring. The leveling to very high aesthetic standards is also detectable in the context of video art.

However, an underground motion is also detectable, still struggling to emerge, and tending toward the return of that feeling of authenticity typical of film. Perhaps we are beginning to tire of the pretense of aesthetic perfection and need to return to the errors, the raw, the real?

Irene Toniolo

Director and Visual Artist

Giulia Lazzaretto

Creative Designer at DrawLight_MeYoung

¹ Not all experimental cinema translates into research linked to the body or to private experience. There are lines of research that investigate the expressive medium and its optical potential. An example is Marcel Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma and there are also numerous examples of research in the field of animated cinema.

Bibliography:

Alessandro Amaducci, Videoarte. Storia, autori, linguaggi, Kaplan, Londra 2014

Philippe Dubois, Video e scrittura elettronica. La questione Estetica, in Valentina Valentini, Il video a Venire, Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli, 1999