BODY AND TECHNOLOGY

The body as the ground for redefining identity

Media art:

The body is at the center of any human activity, including artistic activity, as a tangible element of its presence in the world. The body is the physical form of human identity: to act on it (even simply through “trivial” actions such as getting a tattoo, a piercing, changing hair color or cut…) is to try to redefine the nature of one’s relationship with the world.

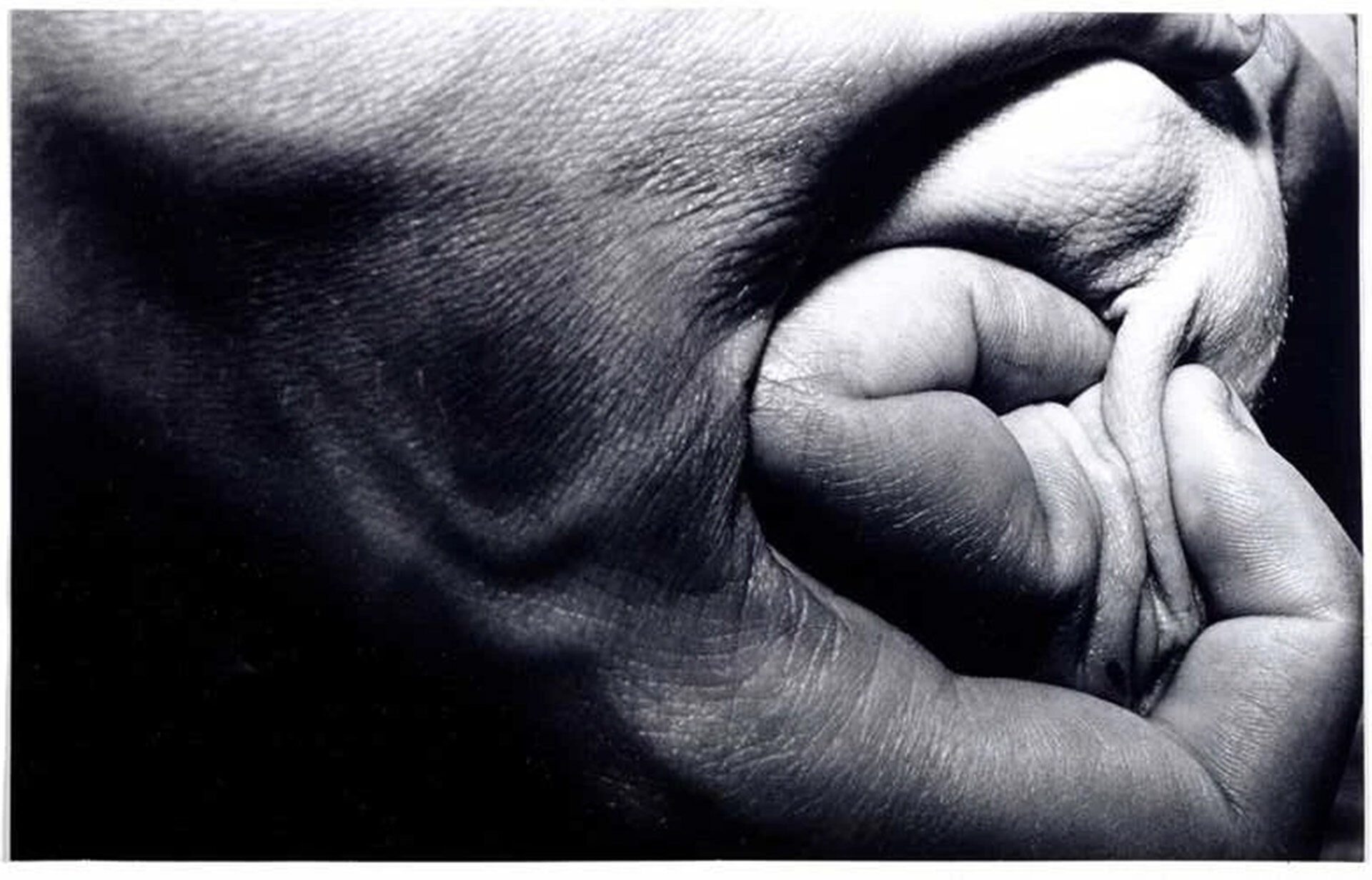

Skin demarcates the boundaries of the self, rooting it in flesh, making itself a frontier between the inside and the outside. It is both an opening to the outside world, thanks to its soft, porous, and absorbent structure, and a limit beyond which one’s inner world is articulated. Nonetheless, it is also an identity structure and a testament to our history through all the marks that characterize it: smell and texture first of all, and then moles, scars, burns, tattoos.

When the other touches our skin, it touches our history, our interiority, our innermost self.

Eva Klasson, Body parts, 1980

Eva Klasson, Body parts, 1980

The body as an artistic tool: Body Art

Body Art was born in the 1960s in response to a series of social and political upheavals that took place and that would come to change the very foundations of society. We are talking about the Vietnam War, the student protest, the civil rights and sufferage movements, sexual liberation and the “discovery” of drugs, and the need to finally do away with the old prevailing morality.

A real earthquake of the general sense of society and existence was taking place; in the artistic sphere, where to start if not from the beginning, that is, the body, as flesh, finally freed from the idea of beauty and shown in all its horror (through the staging of various degrees of injuries, urination, live excretion…)?

The art of those years thus wanted to provoke, to shake, to frighten. It wanted to go against the manicured images of advertising that proposed impersonal, “cartoonish,” in a certain sense even ridiculous bodies, whose aesthetics did not intimidate but rather sought to reassure. The art of those years instead shouted that life was elsewhere. The body was used as the oldest tool to affirm the here and now, the now, without any mediation that would have risked “diluting” the intensity of the protest.

Almost 30 years after the birth of Body Art, a different need developed in the 1990s: a contamination between the body and technology. The extremely rapid technological development seemed to have no limits. New technologies were chasing each other frantically in all spheres; medicine, genetic engineering, biotechnology, robotics, and prosthetic surgery were increasingly making possible the development of a hybrid body, standing somewhere between the organic and the inorganic. Art cannot but be influenced by such discourses and develop works that question the physiognomy of the human body and, therefore, its identity.

Stelarc, The Third Hand, 1980- 1998

Stelarc, The Third Hand, 1980- 1998

Two examples: Orlan e Stelarc

Orlan

Orlan, 1996

Orlan began her artistic activity in the same years in which Body Art was developing, and although she too put the body at the center, she did so in an entirely different way than many of her artistic contemporaries.

As mentioned above, in those years the entire international art world was being swept up in a strong political charge; in France there was the so-called May of ’68, the set of revolutionary movements that occurred between May and June of that year aimed at undermining traditional society, capitalism, imperialism, and the Gaullist power then dominant in France.

The May of ’68 is the fertile ground from which Orlan was born. Her artistic research is based on the concept of identity linked to the image of women, a concept that was, much more than today, under male “domination.”

The canons of beauty imposed, both in real life and in artistic representations, were aimed at pleasing an all-male taste; woman was seen almost as a fetish, harnessed in the stereotypical dichotomous imagery of saint/bitch. Orlan’s body thus becomes a highly politicized, nonconformist, antithetical, and unaesthetic body.

Orlan, Omniprésence. Sourire de plaisir (Smile of Delight), 21 Novembre 1993

Orlan, Omniprésence. Sourire de plaisir (Smile of Delight), 21 Novembre 1993

Orlan’s use of technology is aimed at remarking on these themes in an absolutist and radical way. In addition to the attempt to respond to the need to diminish the distance between being and appearing, her work mainly focuses on the re-definition of the face as the quintessential symbol of Identity.

Her artistic-surgical project involved the grafting of two prostheses, normally used for cheekbone elevation, which she has placed on the sides of the forehead, like small “horns.” The last procedure of this operation was broadcast in real time, via satellite, to various museum sites giving the public a chance to ask questions.

The ritual was de-sacralized. With this act of hers, Orlan “appropriates” the medium of cosmetic surgery, which until then had been considered, by the male capitalist society, the ideal tool for modifying women’s bodies according to a canon of beauty instituted for its own use, making it instead the perfect tool for autonomous identity re-construction. This operation sharply severed the distinction between art and life and by creating a graft of flesh and silicon, a body that lies between the organic and the inorganic.

Stelarc

Stelarc, 1994

Stelarc began his artistic career in the 1970s and immediately began to probe the “geographical” limits of the human body, making videos inside it (specifically in the stomach, colon, and lungs).

The artist is not interested in classical aesthetics, to which art has always been closely attached; he is not interested in appearances, he wants to penetrate the guts, to carp the geography, to cross the blood, the muscles, the organs, the humors. He wants to go beyond the inner/outer dichotomy, he wants to understand what sets the organism in motion, what makes it vibrate, pulsate.

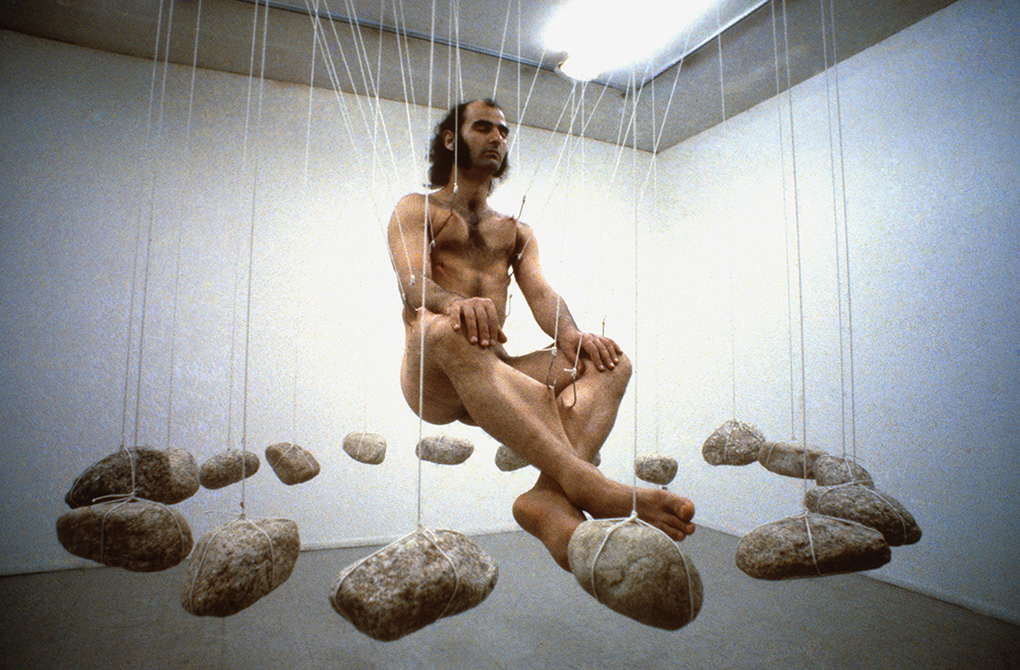

Between 1976 and 1988 Stelarc performed The Body Suspensions, a series of performances in which the artist had his skin pierced by steel hooks and suspended for hours, thanks to the elasticity of the skin, in ever-changing locations. Depending on the situation, between fourteen and eighteen insertion points are required, each coinciding with a point of pain. Preparation for each performance, being very delicate, takes about 40 minutes. At the moment of lifting and lowering again, Stelarc was seized with pain, and it took him about a week to fully recover from his injuries.

Despite how it may seem, there was no mystical charge driving these suspensions of his, but rather a reflection on bodily limitations, as well as an attempt to analyze and go beyond the concept of gravity.

Stelarc, Sitting/Swaying: Event for Rock Suspension, 1980

Stelarc, Sitting/Swaying: Event for Rock Suspension, 1980

Stelarc’s artistic activity is aimed at creating, as he himself says in an interview with Artribune, an alternative anatomical architecture.

In fact, for the artist, the human body has become obsolete, a kind of anachronistic carapace, and only through the use of technology is it possible to modify it to make it more current, with extremely advanced technological grafts and prostheses. The skin, then, becomes pure material to work with.

With him begins a process of aesthetic dematerialization: the increasing and constant presence of technologies in the artistic sphere has changed the common aesthetic perception, moving toward an immaterial and indistinct concept of beauty.

Stelarc, 1994

Irene Toniolo

Director and Visual Artist

Bibliography

Teresa Macrì, Il corpo postorganico. Sconfinamenti della performance, Costa & Nolan, 1997

David Le Breton, La pelle e la traccia. Le ferite del sé, Meltemi, 2016

Donatella Giordano, Architetture anatomiche alternative. Intervista a Stelarc, Artribune, 20/12/2017